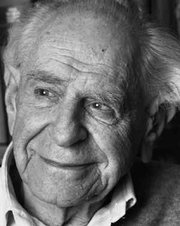

Karl Popper

|

|

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (July 28, 1902 – September 17, 1994), was an Austrian-born, British philosopher of science. He is counted among the most influential philosophers of science of the 20th century, and also wrote extensively on social and political philosophy. Popper is perhaps best known for repudiating the classical observationalist-inductivist account of science; for advancing empirical falsifiability as the criterion for distinguishing scientific theory from non-science; and for his defense of liberal democracy and the principles of social criticism which he took to make the flourishing of the "open society" possible.

| Contents |

Life

Born in Vienna (then Austria-Hungary) in 1902 to middle-class parents of Jewish origins, Karl Popper was educated at the University of Vienna. He took a Ph.D. in philosophy in 1928, and taught in secondary school from 1930 to 1936. In 1937, the rise of Nazism and the threat of the Anschluss led Popper to emigrate to New Zealand, where he became lecturer in philosophy at Canterbury University College New Zealand (at Christchurch). In 1946, he moved to England to become reader in logic and scientific method at the London School of Economics, where he was appointed professor in 1949. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1965, and was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1976. He retired from academic life in 1969, though he remained intellectually active until his death in 1994. He was invested with the Insignia of a Companion of Honour in 1982.

Popper won many awards and honors in his field, including the Lippincott Award of the American Political Science Association, the Sonning Prize, and fellowships in the Royal Society, British Academy, London School of Economics, King's College London, and Darwin College Cambridge. Austria awarded him the Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold.

Popper's philosophy

Popper coined the term critical rationalism to describe his philosophy. This designation is significant, and indicates his rejection of classical empiricism, and of the observationalist-inductivist account of science that had grown out of it. Popper argued strongly against the latter, holding that scientific theories are universal in nature, and can be tested only indirectly, by references to their implications. He also held that scientific theory, and human knowledge generally, is irreducibly conjectural or hypothetical, and is generated by the creative imagination in order to solve problems that have arisen in specific historico-cultural settings. Logically, no number of positive outcomes at the level of experimental testing can confirm a scientific theory, but a single genuine counter-instance is logically decisive: it shows the theory, from which the implication is derived, to be false. Popper's account of the logical asymmetry between verification and falsification lies at the heart of his philosophy of science. It also inspired him to take falsifiability as his criterion of demarcation between what is and is not genuinely scientific: a theory should be accounted scientific if and only if it is falsifiable. This led him to attack the claims of both psychoanalysis and contemporary Marxism to scientific status, on the basis that the theories enshrined by them are not falsifiable. His scientific work was influenced by his study of Albert Einstein's theory of relativity. Popper's falsificationism resembles Charles Peirce's falliblism. In Of Clocks and Clouds (1966), Popper said he wished he had known of Peirce's work earlier.

In Conjectures and Refutations (1963), Popper sought to explain the apparent progress of scientific knowledge—how it is that our understanding of the universe seems to improve over time. This problem arises from his position that the truth content of our theories, even the best of them, cannot be verified by scientific testing, but can only be falsified. If so, then how is it that the growth of science appears to result in a growth in knowledge? In Popper's view, the advance of scientific knowledge is an evolutionary process characterized by his formula:

In response to a given problem situation (<math>PS_1<math>), a number of competing conjectures, or tentative theories (<math>TT<math>), are systematically subjected to the most rigorous attempts at falsification possible. This process, error elimination (<math>EE<math>), performs a similar function, for science, that natural selection performs for biological evolution. Theories that better survive the process of refutation are not more true, but rather, more "fit"—in other words, more applicable to the problem situation at hand (<math>PS_1<math>). Consequently, just as a species' "biological fit" does not predict continued survival, neither does rigorous testing protect a scientific theory from refutation in the future. Yet, as it appears that the engine of biological evolution has produced, over time, adaptive traits equipped to deal with more and more complex problems of survival, likewise, the evolution of theories through the scientific method may, in Popper's view, reflect a certain type of progress: toward more and more interesting problems (<math>PS_2<math>). For Popper, it is in the interplay between the tentative theories (conjectures) and error elimination (refutation) that scientific knowledge advances toward greater and greater problems; in a process very much akin to the interplay between genetic variation and natural selection.

Knowledge, for Popper, was objective, not in the sense that it is objectively true, but rather, that knowledge has an ontological status (i.e.–knowledge as object) independent of the knowing subject (Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972). He proposed three worlds (see Popperian cosmology): World One, being the phenomenal world, or the world of direct experience; World Two, being the world of mind, or mental states, ideas, and perceptions; and World Three, being the body of human knowledge expressed in its manifold forms, or the products of the second world made manifest in the materials of the first world (i.e.–books, papers, paintings, symphonies, and all the products of the human mind). World Three, he argued, was the product of individual human beings in exactly the same sense that an animal path is the product of individual animals, and that, as such, has an existence and evolution independent of any individual knowing subjects. The influence of World Three, in his view, on the individual human mind (World Two) is at least as strong as the influence of World One. In other words, the knowledge held by a given individual mind owes at least as much to the total accumulated wealth of human knowledge, made manifest, than to the world of direct experience. As such, the growth of human knowledge could be said to be a function of the independent evolution of World Three. Compare with Memetics. Contemporary philosophers have not embraced Popper's Three World conjecture, due mostly, it seems, to its resemblance to Cartesian dualism.

In The Open Society and Its Enemies and The Poverty of Historicism, Popper developed a critique of historicism and a defence of the 'Open Society', liberal democracy. Historicism is the theory that history develops inexorably and necessarily according to knowable general laws towards a determinate end. Popper argued that this view is the principal theoretical presupposition underpinning most forms of authoritarianism and totalitarianism. He argued that historicism is founded upon mistaken assumptions regarding the nature of scientific law and prediction. Since the growth of human knowledge is a causal factor in the evolution of human history, and since "no society can predict, scientifically, its own future states of knowledge", it follows, he argued, that there can be no predictive science of human history. For Popper, metaphysical and historical indeterminism go hand in hand.

Among his contributions to philosophy is his answer to David Hume's Problem of Induction. Hume stated that just because the sun has risen every day for as long as anyone can remember, doesn't mean that there is any rational reason to believe it will come up tomorrow. There is no rational way to prove that a pattern will continue on just because it has before.

Popper's reply is characteristic, and ties in with his criterion of falsifiability. He states that while there is no way to prove that the sun will come up, we can theorize that it will. If it does not come up, then it will be disproven, but since right now it seems to be consistent with our theory, the theory is not disproven. Thus, Popper's demarcation between science and non-science serves as an answer to an old logical problem as well.

Influence

By all accounts, Popper has played a vital role in establishing the philosophy of science as a vigorous, autonomous discipline within analytic philosophy, through his own prolific and influential works, and also through his influence on his own contemporaries and students -- chief among them, Imre Lakatos and Paul Feyerabend, two of the foremost philosophers of science in the next generation of analytic philosophy. (Lakatos's work drastically modifies Popper's position, and Feyerabend's repudiates it entirely, but the work of both is deeply influenced by Popper and engaged with many of the problems that Popper set.)

Popper is also widely credited as one of the leading voices in the revolt against the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle in the middle of the 20th century; his revival of Humean skepticism toward induction and his introduction of the principle of falsifiability as a non-inductive solution to the puzzle of scientific knowledge, played a major role in the criticism of the view of science that was central to the positivist programme. Popper, not always known for his modesty, entitled a chapter of his memoirs "Who Killed Logical Positivism?" — a question which he answered by saying "I fear that I must admit responsibility". Popper may have overstated his own influence somewhat vis-a-vis fellow critics of positivism, such as W.V.O. Quine and Popper's philosophical nemesis Ludwig Wittgenstein.

While there is some dispute as to the matter of influence, Popper had a long standing and close friendship with economist Friedrich Hayek, also from Vienna. Each found support and similarities in each other's work, citing each other often, though not without qualification. In a letter to Hayek in 1944, Popper stated, "I think I have learnt more from you than from any other living thinker, except perhaps Alfred Tarski." (See Hacohen, 2000). Popper dedicated his Conjectures and Refutations to Hayek. For his part, Hayek dedicated a collection of papers, Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, to Popper, and in 1982 said, "...ever since his Logik der Forschung first came out in 1934, I have been a complete adherent to his general theory of methodology." (See Weimer and Palermo, 1982).

Popper's influence, both through his work in philosophy of science and through his political philosophy, has also extended beyond the academy. Among Popper's students and advocates is the multibillionaire investor George Soros, who says his investment strategies are modelled on Popper's understanding of the advancement of knowledge through falsification. Among Soros's philanthropic foundations is the Open Society Institute, a think-tank named in honor of Popper's The Open Society and Its Enemies, which Soros founded to advance the Popperian defense of the open society against authoritarianism and totalitarianism.

Critics

The Quine-Duhem thesis argues that it is impossible to test a single hypothesis on its own, since each one comes as part of an environment of theories. Thus we can only say that the whole package of relevant theories has been collectively falsified, but cannot conclusively say which element of the package must be replaced. An example of this is given by the discovery of the planet Neptune: when the motion of Uranus was found not to match the predictions of Newton's laws, the theory "There are seven planets in the solar system" was rejected, and not Newton's laws themselves. Popper discussed this critique of naïve falsificationism in Chapters 3 & 4 of The Logic of Scientific Discovery. For Popper, theories are accepted or rejected via a sort of 'natural selection'. Theories that say more about the way things appear are to be preferred over those that do not; the more generally applicable a theory is, the greater its value. Thus Newton’s laws, with their wide general application, are to be preferred over the much more specific “the solar system has seven planets”.

Thomas Kuhn’s influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions argued that scientists work in a series of paradigms, and found little evidence of scientists actually following a falsificationist methodology. Popper's student Imre Lakatos attempted to reconcile Kuhn’s work with falsificationism by arguing that science progresses by the falsification of research programs rather than the more specific universal statements of naïve falsificationism. Another of Popper’s students Paul Feyerabend ultimately rejected any prescriptive methodology, and argued that the only universal method characterizing scientific progress was anything goes.

Another objection is that it is not always possible to demonstrate falsehood definitively, especially if one is using statistical criteria to evaluate a null hypothesis. More generally, it is not always clear that evidence contradicting a hypothesis is a sign of flaws in the hypothesis rather than of flaws in the procedures used to test it.

Other critics seek to vindicate the claims of historicism or holism to intellectual respectability, or psychoanalysis or Marxism to scientific status. It has been argued that Popper's student Imre Lakatos transformed Popper's philosophy using historicist and updated Hegelian historiographic ideas.

In 2004 philosopher and psychologist Michel ter Hark (Groningen, The Netherlands) published a book, called Popper, Otto Selz and the rise of evolutionary epistemology, in which he claims that Popper got a part of his ideas from his tutor, the German-Jewish psychologist Otto Selz. Selz himself never published his ideas, partly because of the rise of Nazism which ordered him to quit his work in 1933, and the prohibition of referencing to Selz' work.

Influence on popular culture

There is an obscure reference to Karl Popper in the Matrix series of movies : a character called 'The Kid', has a more defined history outlined within an addendum to those films (the Animatrix) where his name is revealed to be Michael Karl Popper. The name chosen may be assumed to be a reference to Popper's own philosophy - not all must be assumed at face value, a vital requirement within the fictional Matrix universe. Also, the actor who plays the part of 'The Kid' has a striking facial resemblance to Karl Popper, which cannot be co-incidental.

See also

- Popperian cosmology

- Evolutionary epistemology

- Liberalism

- Scientific Community Methaphor

- Contributions to liberal theory

- List of Austrian scientists

Bibliography

- Logik der Forschung, 1934 (in German)

- The Open Society and Its Enemies, 1945

- The Logic of Scientific Discovery, 1959 (Translation of Logik der Forschung)

- The Poverty of Historicism, 1961

- Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge, 1963

- Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, 1972

- Unended Quest; An Intellectual Autobiography, 1976

- The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism (with Sir John C. Eccles), 1977

- Die Beiden Grundprobleme der Erkenntnistheorie - Aufgrund von Manuskripten aus den Jahren 1930-1933 (The Two Fundamental Problems of Epistemology - Based on Manuscripts From the Period 1930-1933) (Edited by Troels Eggers Hansen), 1979 (in German)

- The Open Universe: An Argument for Indeterminism, 1982

- Realism and the Aim of Science, 1982

- Die Zukunft ist Offen (The Future is Open)(with Konrad Lorenz), 1985 (in German)

- The Lesson of this Century, Interviewer: Giancarlo Bosetti, English translation: Patrick Camiller), 1992

- The World of Parmenides, Essays on the Presocratic Enlightenment, (Edited by Arne F. Petersen with the assistance of Jørgen Mejer)

- The Myth of the Framework: In Defence of Science and Rationality, 1994

- Knowledge and the Mind-Body Problem: In Defence of Interactionism, 1994

- Quantum Theory and the Schism in Physics, (From the Postscript to The Logic of Scientific Discovery)

- In Search of a Better World, a collection of Popper’s essays and lectures covering a range of subjects from the beginning of scientific speculation in classical Greece to the need for a new professional ethic based on the ideas of tolerance and intellectual responsibility; "All things living are in search of a better world."; Karl Popper, from the Preface

Other works and collections:

- Critical Rationalism: A Re-Statement and Defence by David Miller, 1994

- Popper Selections (Text by Popper, selected and edited by David Miller)

- All Life Is Problem Solving (Text by Popper, translation by Patrick Camiller), 1999

Further reading

- Feyerabend, P. Against Method. London: New Left Books, 1975. A splendidly polemical, iconoclastic book by a former colleague of Popper's. Vigorously critical of Popper's rationalist view of science.

- Kadvany, John Imre Lakatos and the Guises of Reason. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8223-2659-0. Explains how Imre Lakatos developed Popper's philosophy into a historicist and critical theory of scientific method.

- Hacohen, M. Karl Popper: The Formative Years, 1902 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. Central to contemporary philosophy of science is the debate between the followers of Kuhn and Popper on the nature of scientific enquiry. This is the book in which the views of the former received their classical statement.

- Magee, B. Popper. London: Fontana, 1977. An elegant introductory text. Very readable, albeit rather uncritical of its subject.

- O'Hear, A. Karl Popper. London: Routledge, 1980. A critical account of Popper's thought, viewed from the perspective of contemporary analytic philosophy.

- Radnitzky, G., Bartley, W. W., eds. Evolutionary Epistemology, Rationality, and the Sociology of Knowledge. La Salle, IL: Open Court Press 1987. ISBN 0-8126-9039-7. A strong collection of essays by Popper, Campbell, Munz, Flew, et al, on Popper's epistemology and critical rationalism. Includes a particularly vigorous answer to Rorty's criticisms.

- Schilpp, P. A., ed. The Philosophy of Karl Popper, 2 vols. La Salle, IL: Open Court Press, 1974. One of the better contributions to the Library of Living Philosophers series. Contains Popper's intellectual autobiography, a comprehensive range of critical essays, and Popper's responses to them.

- Stokes, G. Popper: Philosophy, Politics and Scientific Method. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1998. A very comprehensive, balanced study, which focuses largely on the social and political side of Popper's thought.

- Weimer, W., Palermo, D., eds. Cognition and the Symbolic Processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1982. See Hayek's essay, "The Sensory Order after 25 Years", and "Discussion".

External links

- Karl Popper (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/popper/) from Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (http://plato.stanford.edu/)

- The Karl Popper Web (http://www.eeng.dcu.ie/%7Etkpw/)

- Karl Popper Institute (http://www.univie.ac.at/wissenschaftstheorie/popper/) includes complete bibliography 1925-1999

- University of Canterbury (NZ) (http://www.phil.canterbury.ac.nz/haps/kiwihps.shtml#popper) brief biography of Popper

- Influence on Friesian Philosophy (http://www.friesian.com/popper.htm)

- Open Society Institute (http://www.soros.org/) George Soros foundations network

- A Skeptical Look at Karl Popper (http://web.archive.org/web/20040212023313/http://www.stephenjaygould.org/ctrl/gardner_popper.html) by Martin Gardner

- Sir Karl Popper: Science: Conjectures and Refutations (http://cla.calpoly.edu/~fotoole/321.1/popper.html)

- Information on Lakatos/Popper (http://www.johnkadvany.com/GettingStarted/Kadvany_Design/Assets/LakatosPage/Lakatos_Frameset_3.htm) Site maintained by John Kadvany, PhD.

An earlier version (http://www.nupedia.com/article/557/) of the above article was posted on 16 May 2001 on Nupedia; reviewed and approved by the Philosophy and Logic group; editor, Wesley Cooper; lead reviewer, Wesley Cooper; lead copyeditors, Cindy Seeley and Ruth Ifcher.bn:কার্ল পপার cs:Karl Raimund Popper da:Karl Raimund Popper de:Karl Popper et:Karl Popper es:Karl Popper eo:Karl POPPER fr:Karl Popper io:Karl Popper id:Karl Popper it:Karl Popper he:קרל פופר nl:Karl Raimund Popper ja:カール・ポパー no:Karl Popper pl:Karl Popper pt:Karl Popper ro:Karl Popper sk:Karl Raimund Popper fi:Karl Popper sv:Karl Popper uk:Поппер Карл zh:卡尔·波普尔